Compassion Fatigue: A Hidden Danger to Veterinary Professionals

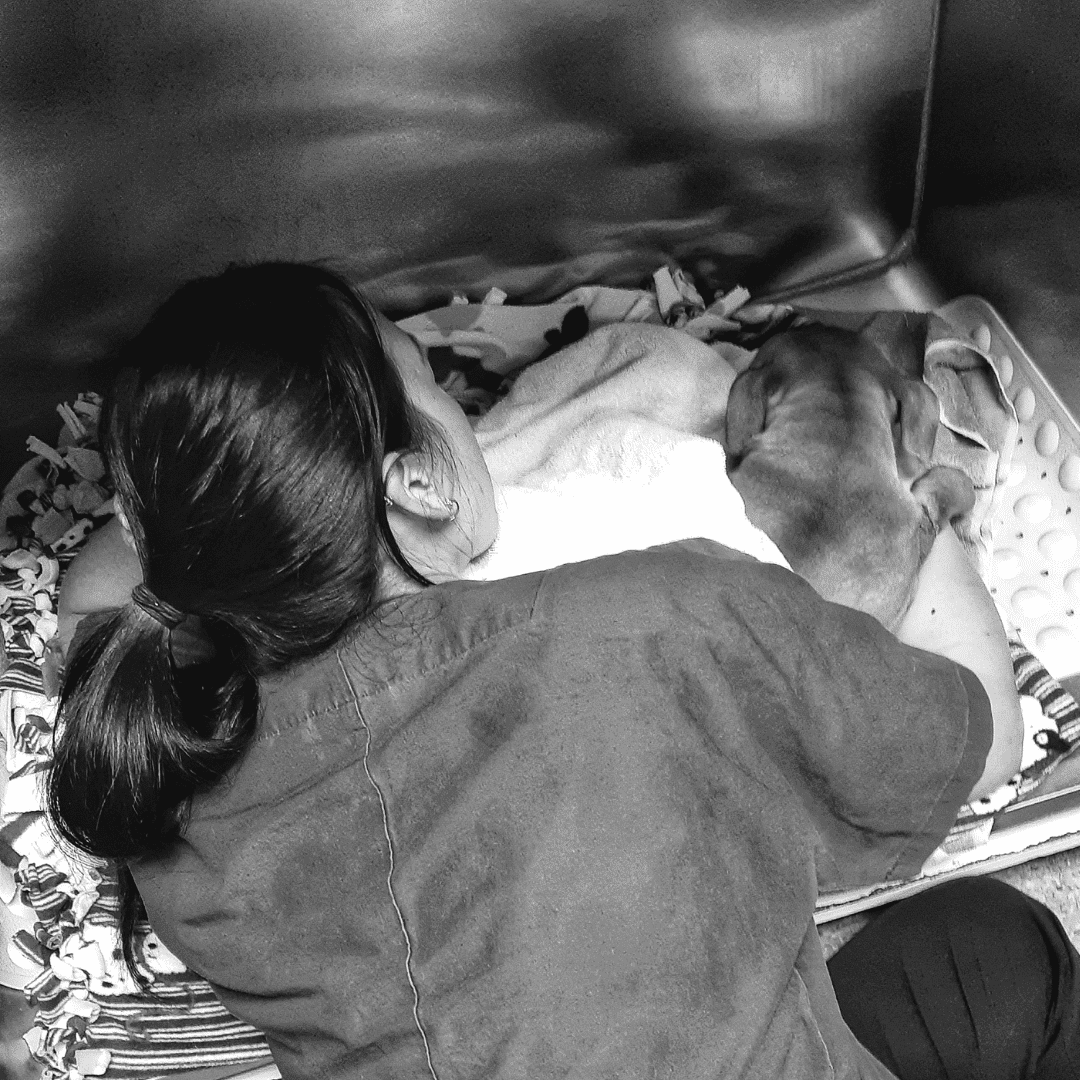

For Sarah,* a thirty-three-year-old veterinarian, the symptoms began in her sixth year of practice. She felt uncharacteristic anger about everyday inconveniences. She believed she never had enough time to fulfill her responsibilities to her job or her family. She struggled to sleep, and when she closed her eyes, images of severely injured patients knifed through her mind. In the mornings, she dragged herself out of bed, completely unrested. Sarah’s exhaustion was noticeable at work, and she became easily frustrated with coworkers. Slowly – secretly – she began to long for an end, to simply disappear.

It was Sarah’s mother who first encouraged her to seek the care of a psychotherapist. After a few sessions, Sarah found an explanation for her symptoms: compassion fatigue.

Compassion fatigue is a state of mental and physical distress that occurs when caregivers are chronically exposed to the suffering of others.1,2,4,12,13 Symptoms of compassion fatigue vary and might include exhaustion, frustration, depression, apathy, headaches, gastrointestinal distress, sleep disturbances, intrusive imagery, and fear.4,15 These negative effects worsen over time if the underlying cause is not addressed. 4,15

Dr. Laurie Fonken, a psychotherapist who specializes in providing mental healthcare for veterinary professionals, has summarized the issue with compassion fatigue in our field: “For those who devote their lives to the service of others, the physical and emotional demands can lead to exhaustion… the natural response may be to work harder, to do more, and to give until there is nothing left to give.” 3

Interestingly, the term “compassion fatigue” is now considered a bit of a misnomer. Compassion is the desire to relieve the suffering of others.3 Compassion involves both the feeling of caring for another and the motivation to relieve another’s suffering.3 Empathy is the ability to take the perspective of another and to feel their feelings as if they were your own.3 Research has shown that it is actually an individual’s ability to empathize, not an individual’s compassion, that becomes fatigued. For this reason, some mental health professionals have suggested replacing the term with “empathetic distress fatigue.”13,14

Why are so many veterinarians talking about compassion fatigue lately?

The short answer is, we’re trying to save lives.

For decades, veterinary professionals have been aware of anecdotal reports of high suicide rates in our field. However, the scientific data backing these anecdotal reports – studies dating all the way back to the 1980s – were not very well-known.6 This changed in the mid-2010s when a cluster of new research articles attracted widespread media attention to the issue.

In 2015 the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report revealed that veterinarians are significantly more likely to experience serious psychological distress, to suffer from depressive episodes, and to consider suicide when compared to the general population.5 In 2019, a study published in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association (JAVMA) showed that veterinarians are significantly more likely to die by suicide compared to the general population.6 Another 2019 JAVMA study showed that both veterinarians and veterinary technicians are significantly more likely to die by suicide compared to the general population.7 The resulting publicity surrounding mental health issues in the veterinary profession stimulated interest in further research and prompted organized veterinary medicine to respond to the problem.

Increasing the awareness of compassion fatigue in our profession is an attempt at intervention. The CDC has outlined several educational targets for suicide prevention. These include coping skills, problem-solving skills, identification of at-risk individuals, and support of at-risk individuals.8 Compassion fatigue has been identified as a risk factor for suicidal ideation and suicide.9,10,11 Therefore, bringing attention to the risks of compassion fatigue is a potential protective measure. This is the first article in a series aimed at doing just that.

A Light in the Dark

Today, Sarah is relieved that she was able to seek mental healthcare when she was struggling. After reducing her clinical hours for a year to recover, Sarah is back to full-time practice once more. She has redesigned her work schedule so that she has more time with her family, and she continues to work with her therapist to build healthy self-care habits. She likens her experience with overcoming compassion fatigue to a spiritual re-awakening. “It was like coming out of a fog,” she says. “I never want to go back to that again.”

Sarah believes that education about the dangers of compassion fatigue would have led her to seek care from a therapist when her symptoms were still relatively mild, and that earlier detection may have reduced her recovery time. She feels that raising awareness regarding the risks of compassion fatigue in veterinary medicine is essential. She also wants to encourage other veterinary professionals to seek both social support and mental health services when they are needed. “Reach out and let others know that you are struggling,” she recommends. “And don’t be afraid to see a therapist if you need help.”

This article is the first in a multi-part series. Part two will focus on the risk factors and warning signs of compassion fatigue.

*Name changed to protect anonymity.

About the Author

Dr. Grider is passionate about promoting mental health in the veterinary field. She is a Certified Compassion Fatigue Professional and is currently completing a master’s degree in Clinical Mental Health Counseling. Dr. Grider is the co-host of IntroVETS, a veterinary podcast by introverts with high-functioning anxiety. Following graduation from Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine in 2008, she practiced as an Associate Veterinarian for eleven years before starting her own veterinary relief business.

References

- American Veterinary Medical Association. (2021). Assess your wellbeing. Retrieved August 28, 2021. https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/wellbeing/assess-your-wellbeing

- Compassion Fatigue Awareness Project. (2021). Retrieved August 24, 2021, from https://compassionfatigue.org/index.html

- Fonken, L. (2019). A view from the edge: Understanding the challenges to veterinary wellbeing. 2019 Pacific Veterinary Conference Proceedings. http://www.vin.com

- Teater, M. & Ludgate, J. (2014). Overcoming compassion fatigue: A practical resilience workbook. PESI Publishing & Media.

- Nett, R. J., Witte, T. K., Holzbauer, S. M., Elchos, B. L., Campagnolo, E. R., Musgrave, K. J., Carter, K. K., Kurkjian, K. M., Vanicek, C., O’Leary, D. R., Pride, K. R., & Funk, R. H. (2015). Notes from the field: Prevalence of risk factors for suicide among veterinarians – united states, 2014. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 64(6), 159.

- Tomasi, S. E., Fechter-Leggett, E. D., Edwards, N. T., Reddish, A. D., Crosby, A. E. & Nett, R. J. (2019). Suicide among veterinarians in the united states from 1979 through 2015. Journal of the american veterinary medical association, 254(1), 104-112. https://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/10.2460/javma.254.1.104

- Witte, T. K., Spitzer, E. G., Edwards, N., Fowler, K. A. & Nett, R. J. (2019). Suicides and deaths of undetermined intent among veterinary professionals from 2003 to 2014. Journal of the american veterinary medical association, 255(5), 595-608. https://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/10.2460/javma.255.5.595

- Stone, D., Holland, K., Bartholow, B., Crosby, A., Davis, S. & Wilkins, N. (2017). Preventing suicide: A technical package of policy, programs, and practices. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/suicideTechnicalPackage.pdf

- Lee, E., Daugherty, J., Eskierka, K. & Hamelin, K. (2019). Compassion fatigue and burnout, one institution’s interventions. Journal of perianesthesia nursing, 34(4), 767-773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jopan.2018.11.003

- Sullivan, S. & Germain, M. (2020). Psychosocial risks of healthcare professionals and occupational suicide. Industrial and commercial training, 52(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-08-2019-0081

- Kleiner, S. & Wallace, J. E. (2017). Oncologist burnout and compassion fatigue: Investigating time pressure at work as a predictor and the mediating role of work-family conflict. BMC health services research, 17, 639. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2581-9

- Joinson C. (1992). Coping with compassion fatigue. Nursing, 22(4), 116-121.

- Dowling T. (2018). Compassion does not fatigue! The Canadian veterinary journal, 59(7), 749–750.

- Klimecki, O. & Singer, T. (2011). Empathic distress fatigue rather than compassion fatigue? Integrating findings from empathy research in psychology and social neuroscience. In: Oakley, B., Knafo, A. & Madhavan, G., et al., editors. Pathological Altruism. New York, New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 1–23. DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199738571.003.0253

- Alvis, D. (2020). Compassion fatigue: Certification training for healthcare, mental health and caring professionals. PESI, Inc.