Compassion Fatigue: Shielding and Healing Yourself

This is part three of a multiple part series on compassion fatigue in the veterinary field.

In his work as a Veterinary Technician Specialist in a small animal referral hospital, Elan* was used to putting in long hours with few breaks. He viewed his ability to handle the demands of his position as a badge of honor. Just before his thirty-fifth birthday, Elan was diagnosed with diabetes. When his doctor recommended new medication and lifestyle changes, Elan grew progressively frustrated. On top of his typical work responsibilities, how was he supposed to find time to eat several small meals and check his blood sugar regularly throughout the day?

Elan struggled to adhere to his doctor’s instructions without adjusting his work schedule, and he soon began suffering from episodes of hypoglycemia related to delaying mealtimes. With these new external stressors, he also began experiencing symptoms of compassion fatigue. He found that he was often irritable at work and had more trouble moving on from emotionally challenging cases. Despite his medical training, Elan’s first impulse was to ignore the doctor’s instructions and discontinue the recommended treatment so that he could get rid of the feeling of constantly being under pressure at work.

After noticing the symptoms of compassion fatigue, Elan found a therapist who helped him identify ways of coping with this new stressful medical diagnosis. Elan realized that he was hesitant to prioritize self-care because of his values surrounding hard work and dedication to his career. He had concerns about requesting health accommodations and feared that he may be labeled as “lazy” by management. Counseling helped him overcome his reluctance to ask for accommodations to his work schedule, and he learned to set healthy boundaries in the workplace. Eventually, Elan was able to negotiate two fifteen-minute breaks and a 1-hour lunchtime each day so that he could properly manage his nutrition and blood sugar. With these accommodations, Elan’s symptoms of caregiver distress improved, and he was able to successfully manage his diabetes. Now, he is accustomed to taking his medication, eating, and checking his blood sugar on a schedule. He is also learning to check in with himself periodically and to monitor how he feels physically and emotionally. This mindfulness practice has helped him identify other changes that would be helpful to his overall wellbeing.

Elan’s case highlights four extremely important factors in successful compassion fatigue management: rapid intervention when symptoms are noted, creation of a personalized intervention plan, a willingness to embrace change, and practicing mindfulness.

Rapid Intervention is Key

Once signs of caregiver distress have been noted, rapid intervention is necessary.1 Thankfully Elan sought help with his symptoms rather than ignoring them or turning to self-defeating behaviors. It is important to remember that symptoms associated with compassion fatigue and burnout worsen over time if the cause is not addressed.1,2 So, if you have noticed signs of compassion fatigue in yourself, now is the time to act!

Self-Care is Essential

Instituting positive self-care habits is the foundation of compassion fatigue management.1 Many people imagine bubble baths, massages, and pedicures when they think about self-care, but this isn’t the whole picture. When therapists and compassion fatigue professionals talk about the use of self-care for managing caregiver stress, we are talking about nurturing both an individual’s physical needs and their core spiritual self. This includes taking steps to ensure that basic life requirements are prioritized – things like adequate amounts of sleep, rest, nourishment, and hydration.

We all must meet our own fundamental needs before we can successfully care for others. However even these “baby steps” may be challenging for veterinary professionals, many of whom don’t spend enough time sleeping or resting, regularly work through lunch, and have trouble finding the time to drink water or even go to the bathroom during the workday. The pervasive ethic of stoicism in the field may discourage veterinary professionals from voicing their needs and concerns. They may also feel a sense of overwhelming duty to their patients and experience guilt when prioritizing their own needs.

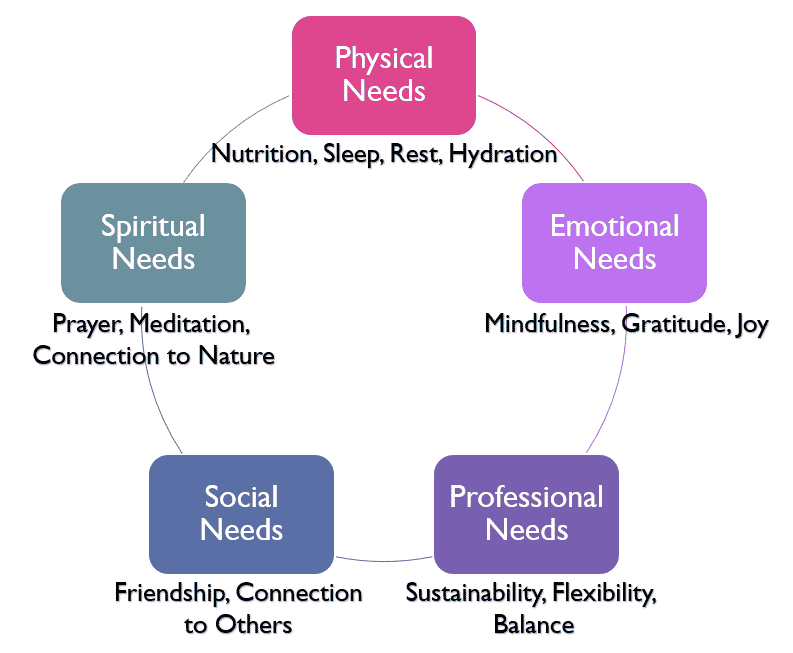

In an attempt to define, cultivate, and promote wellbeing, many interdimensional models of wellness have been proposed. These models are typically used to identify areas of focus for improvement of life satisfaction and contentment. In all models, the dimensions of wellness are interrelated and interdependent.3,4,5,6,7 Similarly, numerous self-care checklists and inventories are available, and they share some common themes including a focus on physical, emotional, professional, social, and spiritual needs. These checklists can be used to create a personalized Self-Care Plan.

Figure 1: Core Self-Care Themes

Self-care plans are a commonly recommended strategy to guard against the effects of compassion fatigue.1 Such a plan should include ideas for meeting physical and emotional needs, as well as a set of strategies for stress reduction. Constructing this type of plan before symptoms occur allows individuals to respond in helpful ways when they begin to experience caregiver stress. To get started on your own checklist, click here to download a customizable version.

Embracing Change

In order to successfully improve self-care habits, individuals must be willing to change.1 Finding strategies to ensure that your needs are met takes some mental flexibility. If self-care were easy, everyone would do it! There are often very real barriers to engaging in healthy behaviors. Removing those barriers requires brainstorming and the formation of a list of multiple options.

In the case above, Elan struggled with the idea of asking for workplace accommodations because he feared the response he would receive. If he had been reluctant to confront and challenge his own beliefs surrounding his professional duties, he would not have found the courage to ask for help, and he would not have gotten the resources he needed to be successful.

Practicing Mindfulness

Mindfulness, or focused awareness of the present moment without judgement or evaluation, has been identified as a useful tool to reduce caregiver stress.1 Practicing mindfulness has been associated with decreased compassion fatigue, burnout, and stress. Improved mindfulness has also been positively correlated to increased life satisfaction and self-compassion.

For Elan, mindfulness is an important part of the ongoing management of his compassion fatigue. His improved awareness of how he is feeling provides important feedback regarding changes he may need to consider for his mental and physical health.

Mindfulness as an intervention for compassion fatigue is an exciting area of research! The next part of this series will include a deep dive into the studies on mindfulness and an exploration of a variety of mindfulness methods.

This is part three of a multi-part series on compassion fatigue in veterinary medicine. The next part will focus on improving mindfulness.

About the Author

Dr. Grider is passionate about promoting mental health in the veterinary field. She is a Certified Compassion Fatigue Professional and is currently completing a master’s degree in Clinical Mental Health Counseling. Dr. Grider is the co-host of IntroVETS, a veterinary podcast by introverts with high-functioning anxiety. Following graduation from Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine in 2008, she practiced as an Associate Veterinarian for eleven years before starting her own veterinary relief business.

References

- Alvis, D. (2020). Compassion fatigue: Certification training for healthcare, mental health and caring professionals. PESI, Inc.

- Teater, M. & Ludgate, J. (2014). Overcoming compassion fatigue: A practical resilience workbook. PESI Publishing & Media.

- Fonken, L. (2019). Living between the lines: Life, work and wellbeing. 2019 Pacific Veterinary Conference Proceedings. http://www.vin.com

- National Wellness Institute. (2020). Retrieved August 28, 2021, from https://nationalwellness.org/resources/six-dimensions-of-wellness/

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (n.d.). Creating a healthier life: A step-by-step guide to wellness. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Swarbrick, M. (2006). A wellness approach. Psychiatric rehabilitation journal, 29(4), 311-314. https://doi.org/10.2975/29.2006.311.314

- The Ohio State University Office of Student Life Wellness Center. (2021). Retrieved August 28, 2021, from https://swc.osu.edu/about-us/nine-dimensions-of-wellness/